Beijing Silvermine: An Inquiry into the Power of Photography and the Nature of Memory

Thomas Sauvin: Beijing Silvermine (Copyright © Beijing Silvermine)

Words by Liv Franks

Photographs capture moments, moments become memories, and memory is under attack. It’s always been fallible to the passage of time, but now, in this epoch of misinformation, our collective memories face digital manipulation, archival hacking, and political posturing. That's why we need to continue using analogue photography, and why you will find Thomas Sauvin in rubbish heaps. For sixteen years now, Beijing-based French photographer Thomas Sauvin has been working with waste. He can be spotted in the grey suburbs of Beijing carrying sacks. They are packed full with photographic negatives because Sauvin has a project to run and a collective memory to protect.

Our memories are flawed things. They are not a reliable source. One year, you will remember an event in a particular way, and the next, you may have added to, lost or entirely warped this memory. That’s one reason why we rely on photography. It’s a static, concrete representation of the intangible. On an individual and collective level, we can return to a photo when something as fragile as our memory has begun to waver. Through his project, Beijing Silvermine, Thomas Sauvin resuscitates the lived experience of thousands of anonymous Chinese families and adds them to the fabric of collective memory.

Thomas Sauvin: Beijing Silvermine (Copyright © Beijing Silvermine)

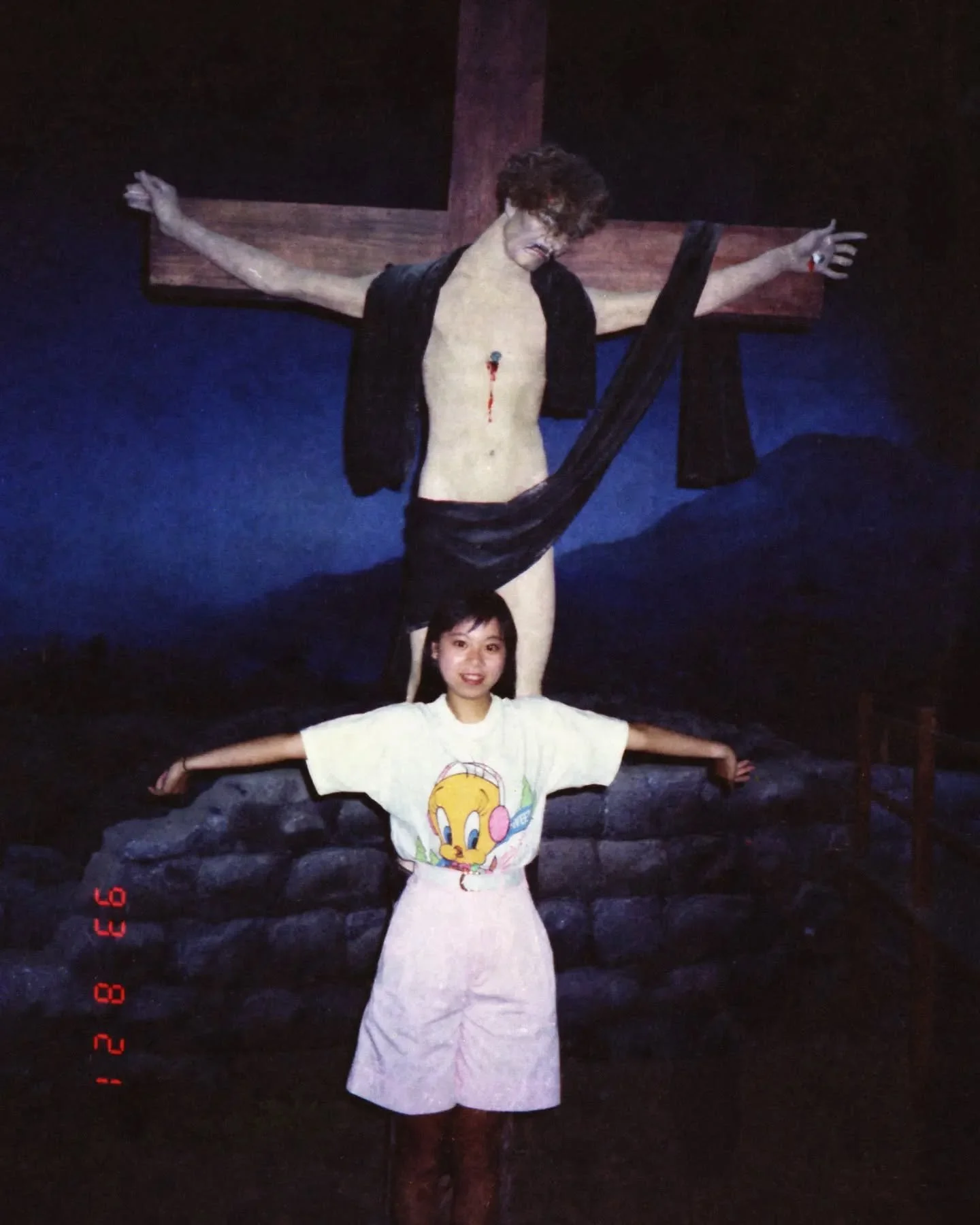

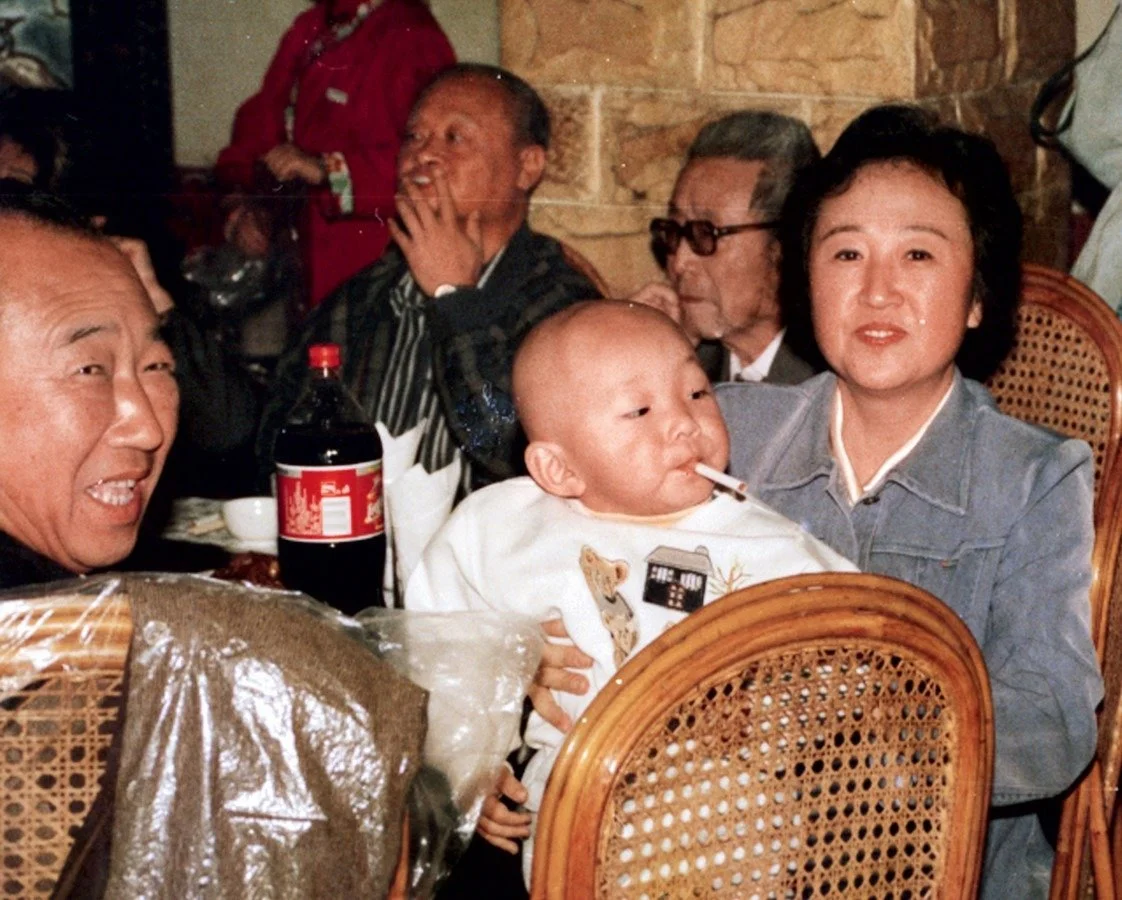

“When we think about the 80s and 90s, it’s a time in Chinese history where people started to consume more, while opening their culture to the rest of the world. These are the kinds of things that you would quite naturally document through photography.”

Thomas Sauvin: Beijing Silvermine (Copyright © Beijing Silvermine)

Beijing Silvermine began in 2009 and continues to this day. Essentially, Sauvin works with informal recycling plants to receive discarded photographic negatives, which he sifts through and digitises. Negatives are kept by rubbish collectors due to their valuable silver nitrate content, but Thomas Sauvin sees the value in the previously unseen photos. At this point, he believes he has collected close to one million 35mm colour film negatives. Focusing on a twenty-year period starting in the 1980s, Beijing Silvermine documents the post-cultural revolution era in China that saw the rise of leisure culture and individual economic agency. The content ranges from the monumental to the mundane. Birthdays, families on the sofa and weekend trips to the newly opened Ronald McDonald statue all make regular appearances on Sauvin’s light table. More importantly, if it were not for the project salvaging these negatives, each of these photos would have been buried beneath Beijing and all the memories they depict along with them.

Thomas Sauvin: Beijing Silvermine (Copyright © Beijing Silvermine)

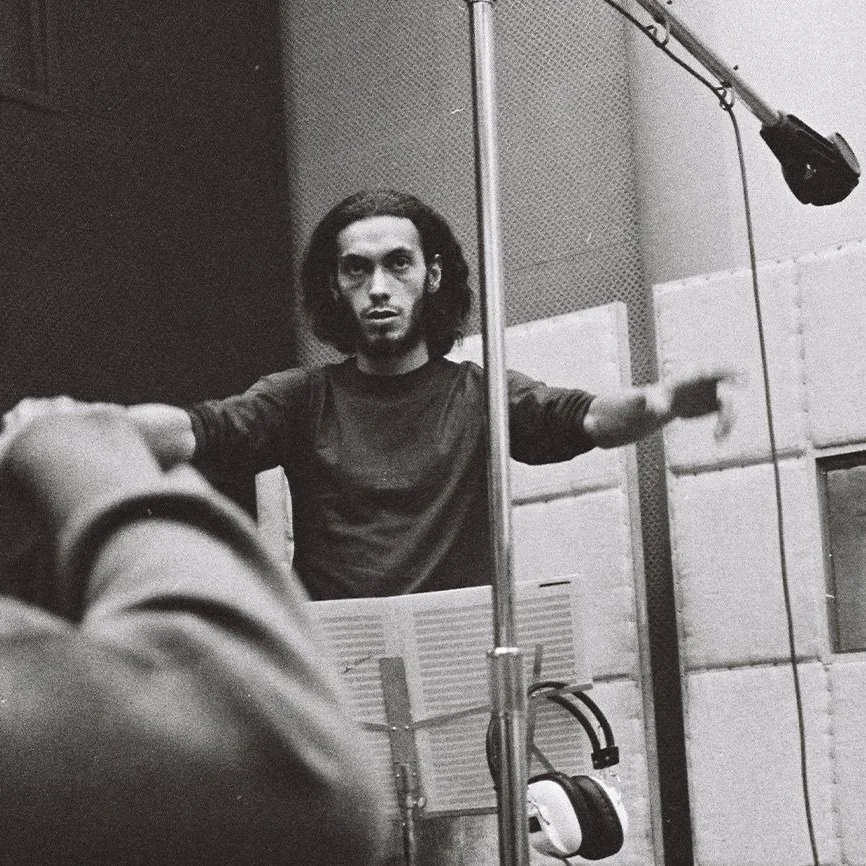

“Perhaps what’s most important to me, is that people are quite surprised that an entire piece of history can be told by everyday people through photography, when generally speaking, it’s widely understood that history is written by the communications department.”

Thomas Sauvin: Beijing Silvermine (Copyright © Beijing Silvermine)

From sacks, Sauvin and his assistant Wanglian remove the unusable negatives and study the rest on a light table. After sending his selected samples to Xiao Wang to be digitised, each photo is given it-s own plate, number, and is archived. Each memory crystallised within the discarded frame is saved and shared. It is added to the growing collaborative narrative of the post cultural revolution period in China.

Sauvin is conscious not to impose any personal bias on this narrative. He just attempts to build connections through recurring patterns (one such pattern is watermelons, another is pigeons) and then lets the photos tell their own tale. In his 2012 documentary, Sauvin points out the frequent appearance of a replica Grand Canyon waterfall, found in Beijing’s World Park. Though many photographs centre on the waterfall, each perspective tells a slightly different story. Sauvin reveals that you can often gauge the playfulness, humour and style of the photographer in this way. Moreover, this speaks to how differently individuals experience the same thing and why collaboration is needed to build the most accurate portrait of a memory.

Thomas Sauvin: Beijing Silvermine (Copyright © Beijing Silvermine)

“The Silvermine archive now counts over 700000 negatives and the greatest shame of all would be for me to interact with these on my own.”

Thomas Sauvin: Beijing Silvermine (Copyright © Beijing Silvermine)

Photography can unite fragmented narratives through a collaborative truth of what happened at that precise moment in time. It’s why media is monitored and manipulated by authoritarian governments. They wish to control the collective memory of an era. Therefore, Thomas Sauvin’s decision to exhibit “vernacular Chinese photography” is a crucial development. He is proving the depth of the individual experience in the post-cultural revolution period. People had disposable income and the agency to choose what to do with it. Along came a burgeoning consumption and leisure culture that had been unavailable in the decades prior. Holidays, new cars, and Western products abound. Of course, we can’t ignore the fact that this isn’t journalistic photography—these people knew their photo was being taken, probably for their friends and family to see what a great time they were having. So, the content of Beijing Silvermine cannot be held up as a holistic historic document, but that doesn’t diminish the project’s value either. Rather, Sauvin sees it as a “portrait of a time and a place”. People possessed point-and-shoot cameras for the first time, and so naturally they chose to depict the good. Essentially, photography was a mode of celebration in 1980s and 1990s China. Wanglian, Sauvin’s project assistant, emphasises the importance of documenting this time. She believes that collectors have neglected this contemporary era of Chinese history in favour of turn-of-the-20th-century pieces, despite it being an undeniable period of rapid change.

Thomas Sauvin: Beijing Silvermine (Copyright © Beijing Silvermine)

Thomas Sauvin: Beijing Silvermine (Copyright © Beijing Silvermine)

What they have found has piqued the interest of younger artists, too. Sauvin has begun collaborating with Chinese artist Lei Lei to make animated videos of the recovered photographs. Paradoxically, Lei Lei is particularly fascinated by the uniformity of individual experience. Lei Lei’s video Recycled (2013) demonstrates how individual and collective experiences interweave with one another. To do so, Lei Lei finds photos that mirror one another’s composition, whether it be people posing in front of a sunset, on a beach, perched on a Buddha statue or in Tiananmen Square, and lays them on top of each other in rapid succession. The different perspectives of the same thing collapse in on each other until it feels like there is only one photographer. Thousands of strangers are united under a collective experience that they did not even know they were sharing. Their “anonymous humanity” depicted in Lei Lei’s short film is symptomatic of the struggle between the individual and collective experience. Each person attempts to find their own way, and wants to document that as proof to themselves and others as having been able to do so, yet it is this very process that ties them to their fellow man.

This theme has evidently resonated with audiences. Sauvin won the prize for the Exhibition of the year at Lianzhou Photo Festival in 2013. Moreover, his work has been exhibited at the Museum of Contemporary Photography of Chicago, the Beijing Central Academy of Fine Art, and the Guangdong Museum of Art. Equally, Lei Lei’s film is the winner of Grand Prix shorts-non-narrative at the 2013 Holland International animation film festival and placed as Officially Selected at Annoy International Animation Festival.

Despite the acclaim, Sauvin’s project stretches before him as an increasingly difficult task. The rise of the digital camera means that there are less and less negatives in existence. Since the 1990s, it has been cheaper and quicker to use a digital camera. Indeed, digital cameras have outsold film cameras year on year since 2003. Fast forward to the present day and the advent of smart phones means that nowadays you possess your photo album without ever actually holding a print. Although Sauvin’s collaborator, Xiao Wang, still digitalises approximately 9,000 photos a month, Sauvin believes that “this project will witness the death of analog photography in China”.

Thomas Sauvin: Beijing Silvermine (Copyright © Beijing Silvermine)

Thomas Sauvin: Beijing Silvermine (Copyright © Beijing Silvermine)

If Sauvin’s prediction is correct, then we could be facing a slippery slope. Without the physical copies generated from analog photography, our photographs will only exist digitally. A digital copy of a memory risks becoming something less trustworthy than a physical copy given the increasing powers of AI and editing tools to convincingly manipulate photographs. If memory was already an imprecise medium, then the lack of physical evidence in the form of analog film leaves it vulnerable to manipulation. That is to say, an authentic collective memory remains under threat from those that wish to control the narrative. Regimes no longer need to raid homes and burn personal archives, they will simply access your online cache of photos and change them. That is why projects like Beijing Silvermine are vital. Tangible archives that act both as memory portals to the past and bulwarks to the future of misinformation.