White-Clothed People: The Hanbok and Korea

People wearing white hanbok c. 1906/1907 Photograph courtesy of the National Folk Museum of Korea

Words by Katherine Elliott

The wearing of white clothing, in particular of white hanbok, was a widespread practice in Korea until the mid-twentieth century. Sometimes referred to as minbok, which translates to “clothing of the people”, this tradition was adhered to by all ages, irrespective of social class, with exceptions for special occasions or in the case of certain professions requiring a uniform. Although Koreans were not the only culture to value white clothing, the wearing of white hanbok was unique in its commitment to such minimalist attire, completely unmarred by coloured accessories or clothing. Indeed, the prevalence of white hanbok was closely tied to conceptions of Korean national identity, with ethnonationalist terms like paegŭiminjok and paegŭidongpo both signifying “white-clothed people”.

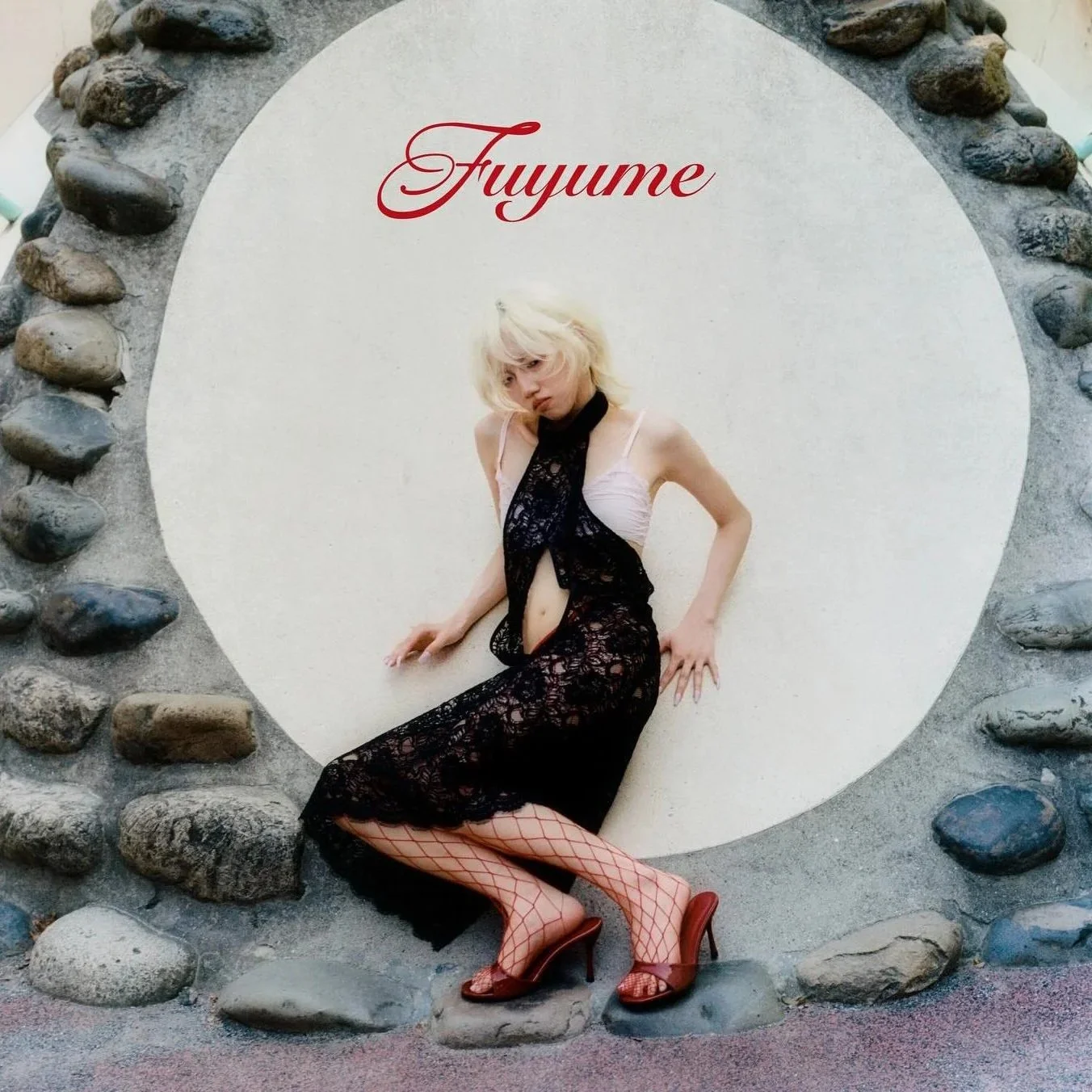

Photography by Min Hyun-woo

References to this tradition extend as far back as the 3rd century. Chen Shou’s historical text, Records of the Three Kingdoms, states that “In Buyeo [an ancient kingdom located in modern-day northeastern China that is seen to a certain extent as a predecessor of Korea], white clothing is revered, so they wear wide-sleeved dopo and baji made from white linens”. This penchant for white hanbok is extensively recorded in contemporary sources, ranging from historical texts like that of Chen Shou to artistic depictions of wrestlers to 19th-century European travel writing to 20th-century photography. It is evident that this custom was widespread throughout the Korean peninsula, yet its origins are not quite as clear.

A laundry spot by the Daedong River, Photocard, 14.2 cm x 9 cm, Busan Museum

Interpretations of the significance of white hanbok vary widely depending on the beholder. A practice that was frequently subject to colonial regulations, the wearing of white clothing was seen by the Japanese imperial authorities as symbolic of mourning and an assumed penchant for pathos. This purported connection between white and mourning was mirrored in R. V. Laguerie’s 1898 account of a visit to Korea in his book La Corée in which “everyone walked slowly and heavily, all in white”. Laguerie’s description represents people in a state of stasis, yet the practicalities of such a sartorial choice hardly allow for such a passive interpretation to be taken at face value. From a purely practical point of view, the constant maintenance required in the daily wearing of a white hanbok was no mean feat. In fact, criticism of this practice ranged from its impracticality to its maintenance requiring Korean housewives to spend copious hours doing laundry; some contemporaries decried this tradition as one of backwards isolationism and argued in favour of “modern” Western clothing. Whilst few would argue that removing stains from white clothing is not an arduous task, to characterise the wearing of white hanbok as the stubborn tradition of a mourning people would be a gross oversimplification.

A young 'kisaeng' (singing girl) in full Korean traditional dress ca. 1904 Photograph courtesy of the Cornell University Library

It is evident that, despite being subject to various criticisms and Japanese assimilation policies, this is a tradition that thrived until the mid-twentieth century. Contrary to assumptions of mourning, traditional interpretations of the colour white have tended to represent purity, nobility, honesty and simplicity. It is also helpful to think in terms of the prevailing religious and philosophical influences of the time. Confucian principles surrounding the suppression of individualistic feelings and emotions led to the colour being seen as symbolic of desires that should ultimately be repressed. The teachings of Buddhism encouraged the pursuit of self-control and emptiness, perhaps reflected in the unadorned white hanbok donned by the Korean masses. The nature of the cloth worn by Koreans is also of significance. As Ernst Oppert notes in his 1880 text Ein verschlossenes Land, Reisen nach Corea, the majority of people wore clothes made of cotton grown in Korea, the most widely used fabric is the coarsely woven hemp cloth’. Whilst Oppert is infamous for his failed 1867 attempt at robbing Prince Namyeon’s tomb in the hopes of blackmailing the then-isolationist Korean monarchy into opening up to foreign trade, his observations reflect the influence of Taoism’s nature-focused principles. The white clothing worn daily by most Koreans was the colour of organic cotton, unaltered by man-made dyes or adornments, in proximity to the purity of nature; perhaps a reflection of these noble Tao values.

Han Young Soo, Hangang River, Seoul, Korea 1958

However, what is most remarkable about this phenomenon is its fierce and collective maintenance. Even today, although the universal tradition has dwindled, white hanbok continues to be worn by shamans, in folk plays; by anti-establishment protestors and progressive politicians, often associated with resistance. Whilst outright displays of Korean nationalism were, particularly under Japanese occupation, violently suppressed, the phenomenon of the white hanbok survived. In the face of forced assimilation, massacres, the practices of forced labour and sexual slavery, this daily act of resistance survived in Korea until the 1950s. The wearing of white hanbok, woven from Korean cotton, free of dyes, arguably encapsulates this idea of Korean national identity as fiercely independent, even in the face of various invasions and occupations; an untarnished sense of solidarity.

Photography by Cho Gi-Seok

Today, the most striking remnants of this widespread tradition remain in works of art and photographs. Kandinsky, a pioneer in Western abstract art, remarked that the colour white “acts on our souls like a great absolute silence… It is a silence that is not dead, but pregnant with possibilities. White has the appeal of the nothingness that is before birth, of the world in the ice age.” Perhaps, it is this association with the endless possibility of a blank canvas prior to contact from the artist that evokes such a response from the viewer in the face of images like Market Day. The photograph shows a busy street filled with shoppers shrinking into the distant midpoint of the image. Each individual, identities lost to time, is cloaked in a gleaming white canvas. It is worth noting that each person’s hanbok is spotless, not a stain in sight.

A market day in a countryside town (1906-7), Photograph, 13.8 cm x 9.3 cm, National Folk Museum of Korea

In her memoir Hold Still, photographer Sally Mann suggests that photography is no substitute for truth, it cannot fully depict an experience lived in that moment; “Photographs economise the truth; they are always moments more or less illusorily abducted from time’s continuum.” If this is the case, how can a modern viewer possibly reconcile visuals of this lost tradition with the multi-hued dress of our times? How can we process the forlorn look of the woman dressed in white at the centre of a photograph by Han Youngsoo?

Taken in Sogong-dong in Seoul around 1956-7, this image is “abducted from time’s continuum” in the years when the tradition of white hanbok, for the most part, disappeared. This unidentified woman dominates the foreground of the image; steadfast where her contemporaries are blurred, clothed in white from head to toe, in contrast to those around her in various degrees of non-white clothing. Perhaps it is Kandinsky’s judgement of white as “pregnant with possibilities” that is the most helpful in our relationship with a mostly vanished tradition. This endless range of interpretations by a modern viewer is in line with the garment’s own range of meanings. The uniform white hanbok worn by Koreans over centuries offered its wearers infinite possibilities of expression; whether aligning the wearer with religious or philosophical principles, maintaining a practical consumption of local material or silently demonstrating a sense of Korean solidarity in the face of occupation and violence. The blank white hanbok allowed its wearer to express the inexpressible.

Han Youngsoo, Sogong-dong, Seoul, Korea, 1956-57