A Phantasy Guide to Japanese Photo Books

Ba-ba Bakuhatsu! Takayama Inari Jinjya, Aomori, 1970, ©Masatoshi Naito

Text by Moe Wang

There’s something thoughtful about Japanese photo books that one senses even before flipping open their covers. It lives in the details of cover design, typography, titles, and the texture of the paper, long before our eyes meet the images. Unlike in the West, where an individual print is often regarded as a standalone artwork, photo books in Japan are conceived as a cohesive whole: image sequencing, binding, printing techniques, and text together form a singular art object.

Once a poetic propaganda tool that documented the social shifts of postwar Japan, Japanese photobooks have since turned inward, becoming vehicles for photographers to inflect their intimate worlds and lived experiences.

As photographers followed their experimental instincts and personal visions, they captured a uniquely Japanese identity in the process. What follows is Phantasy’s guide to 14 cross-generational Japanese photobooks that reflect multilayered sensibilities—where personal visions explore themes ranging from self-identity and desire to nature and the nuances of everyday life.

girls blue, 1996, ©Hiromix

girls blue by Hiromix (1996)

In Japan, blue evokes the feeling of teenage youthfulness and energy. True to its name, girls blue is a compilation of 122 lively images of girlhood seen through the eyes of Toshikawa Hiromi. The book traces the lifestyle of young Tokyoite girls amid the pop consumerism of 1990s Tokyo, dominated by shopping malls, fashion, fast-food outlets, and flirtations with boys. Within this vibrant sprawl of teenage life, Hiromix becomes both documentarian and close participant, candidly capturing the buoyancy and arrogance of youth.

Untitled (Erotos), 1993, ©Nobuyoshi Araki

Erotos by Nobuyoshi Araki

The throbbing red cover is paired with the simple title, EROTOS, in what reads like an alarm bell for what lies beneath. Coined by Nobuyoshi as a combination of Eros and Thanatos, the book compiles his findings of sexuality embedded in everyday life: an overripe fig, a half-bitten pomegranate, close-up shots of cicadas, and the oral cavity. By deliberately placing erotic images of female figurines alongside still lifes of food and animals reminiscent of the human body, Nobuyoshi sought to push against the sexual taboos surrounding female bodies in postwar Japanese society.

Utatane, 2001, ©Rinko Kawauchi

Utatane by Rinko Kawauchi

Floating soap bubbles, swarming carp, and spinning washing machines are suspended in a state of gentle motion in Utatane (Japanese for light nap), one of Kawauchi’s indelible works. The juxtapositions of images across facing pages feel quietly connected, despite their apparent randomness. Close-up shots of a grandfather’s fingers, flashes of lightning, a glass of water, and a splitting watermelon trace Kawauchi’s attentive observation of everyday life. Through her gaze, these moments take on a fading, nostalgic tone, bathed in cool, icy blue.

Showa 88, 2012, ©Kazuyoshi Usui

Showa 88 by Kazuyoshi Usui

Usui imagines a future in which the Showa era (1926-1989) continued uninterrupted into the present, stretching across 88 years. In this book, he gathers the lingering remnants of Showa culture as it exists today, turning his lens toward Osaka’s poor Nishinari and Tobita Shinchi districts, Kyoto’s Gojo-Rakuen area, Chiba Prefecture’s Sakae City and several other locations. The result is an overly saturated parade of traveling performers and freak shows, yakuzas, and young geisha girls drifting through the mundane corners of streets and storefronts, all washed in a saccharine pink tone.

Portrait of J, 2025, ©Takashi Homma

Portrait of J by Takashi Homma

Ordinary Japanese residents take centre stage in Homma’s latest photo book. Turning his lens toward his hometown of Tokyo, the photographer dedicates the series to the people who live there, taken between 2002 and the present. Friends and families are photographed across varied yet familiar urban settings, from subway stations to cluttered kitchens. Set apart from the seminal works of Wolfgang Tillmans’ Portraits, August Sander’s Face of Our Time, and Irving Penn’s Small Trades, Portrait of J carries an overarching softness—guided by Homma’s desire to observe the people who make up contemporary Japan as they are.

Project Family, 2013, ©Motoyuki Daifu

Project Family by Motoyuki Daifu

Like father, like son, Daifu perhaps traces his earliest photographic roots to his father, who was also a professional photographer. In Daifu’s world, however, his father—along with his mother, four siblings, and the cat—becomes the subject of his lens. The series captures the gleeful mess and domestic chaos unfolding inside the family’s compact five-bedroom home in Yokohama. Vibrant clutter fills the frame, creating an unfiltered snapshot of the intimacy and mundanity of everyday life in a Japanese household.

Yellow Sea, Cheju, 1992, ©Hiroshi Sugimoto

Seascapes by Hiroshi Sugimoto

Tranquility speaks to the void in Hiroshi Sugimoto’s Seascapes series. Ocean and sky, bisected by a crisp horizon, occupy the centre of each image, rendered in black and white. For the photographer, who left his native Japan in 1970 to study photography in California and later settled in New York City, the sea becomes a projection of an ever-shifting identity, suspended between different lands, cultural spheres, and countries. “Every time I view the sea, I feel a calming sense of security, as if visiting my ancestral home,” Sugimoto writes of the series. “I embark on a voyage of seeing.”

mama love, 2008, ©Hideka Tonomura

mama love by Hideka Tonomura

When Tonomura learned of her mother’s love affair, her instinct as a photographer was to document it. The book, which is the republication of its initial release in 2008, captures some gripping moments of Tonomura’s mother in bed with her lover, rendered in ominous monochrome. With the lover obscured in total blackout—reduced to an unknown, dark entity—the focus shifts entirely to the mother: her expressions, gestures, and pleasure. In one image, her mother returns a piercing gaze to the camera. “I was surprised when I saw how the photos came out,” writes Tonomura of the series. “My mother was looking at the camera.”

Hotaru, 2013, ©Yoshio Mizoguchi

Hotaru by Yoshio Mizoguchi

“At some point in my life, I had come to think of women as being comparable to fireflies,” writes Mizoguchi of his photo book Hotaru (Japanese for fireflies). “When the sweet nectar of my youth was gone, I took a camera as my new firefly scoop and decided I would capture new fireflies.” Across 126 pages, portraits of girls and women of all ages in Japan, taken from the early 1990s through the 2000s, flutter through quiet moments—resting beneath trees, playing in parks, sitting across tables, and lingering on benches. Here, the self-taught photographer seeks to capture moments of passion and soft sensuality as he perceives them in women.

Tokyo Dolls: Blue Flower, 1980, ©Hiromi Tsuchida

Tokyo Dolls: Blue Flower by Hiromi Tsuchida

Captured between 1972 and 1980, the photo book portrays Tokyo’s transgender women with vivid colour and unapologetic presence, set against richly vivid interior backdrops. Dressed in risque outfits, striking poses, and at times photographed nude, the subjects return the camera’s gaze with confidence, as if confronting their own reflections in a mirror. The compilation brings together eight years of Tsuchida’s intimate portrait-making, tracing queer lives in Japan with tenderness and resolve.

Self-Portraits, 2020, ©Yurie Nagashima

Self-Portraits by Yurie Nagashima

Spanning 24 years, Nagashima places herself at the forefront of the work, tracing her life from student, backpacker, and artist to motherhood. The images are sequenced chronologically, allowing gradual shifts in her appearance and age to unfold alongside changes in her photographic interests, style, and aesthetic. Her early series of nude portraits with her family questions the male gaze and the role of the nude female body in photography. In later works, following the birth of her son and the 2011 Fukushima nuclear accident, her images take on a distinctly feminist and political dimension.

Baba: Tohoku no Minkan Shinko, 1979, ©Masatoshi Naito

Baba: Tohoku no Minkan Shinko by Masatoshi Naito

Some may say Naito was more ethnographer than a photographer. A chemist-turned-freelancer, he became interested in the folklore of the Tohoku region after encountering the mummified remains of Buddhist monks in Yamagata Prefecture. Since then, his photographic practice has centred on capturing the folk beliefs embedded in the mountains of northern Japan. This book documents the people and mystical auras of this enclave, believed to be inhabited by spirits. Using a powerful strobe light that pierces deep into the darkness, Naito vividly captures the faces of local babas (Japanese for hags) who place robust faith in the life forces of the Tohoku land.

Takenokozoku, 2024, ©Noriko Shibuya

Takenokozoku by Noriko Shibuya

With its title rendered in playful fonts that resemble youthful, spiky bamboo shoots, this photobook serves as a visual document of the takenokozoku, a radical youth movement that swept through Harajuku in the late 1970s and 80s (takenoko meaning bamboo shoots in Japanese). When Harajuku’s pedestrian zone opened on Sundays in the 1980s, young people in brightly colored, extravagant outfits flooded the Olympic Road, dancing to full-volume disco music and Yellow Magic Orchestra’s “Rydeen.” Sourcing their clothes from Boutique Takenoko, the group took on its name. In this book, Shibuya captures the fashion, energy, and collective enthusiasm that enraptured both youth and onlookers during this vibrant era.

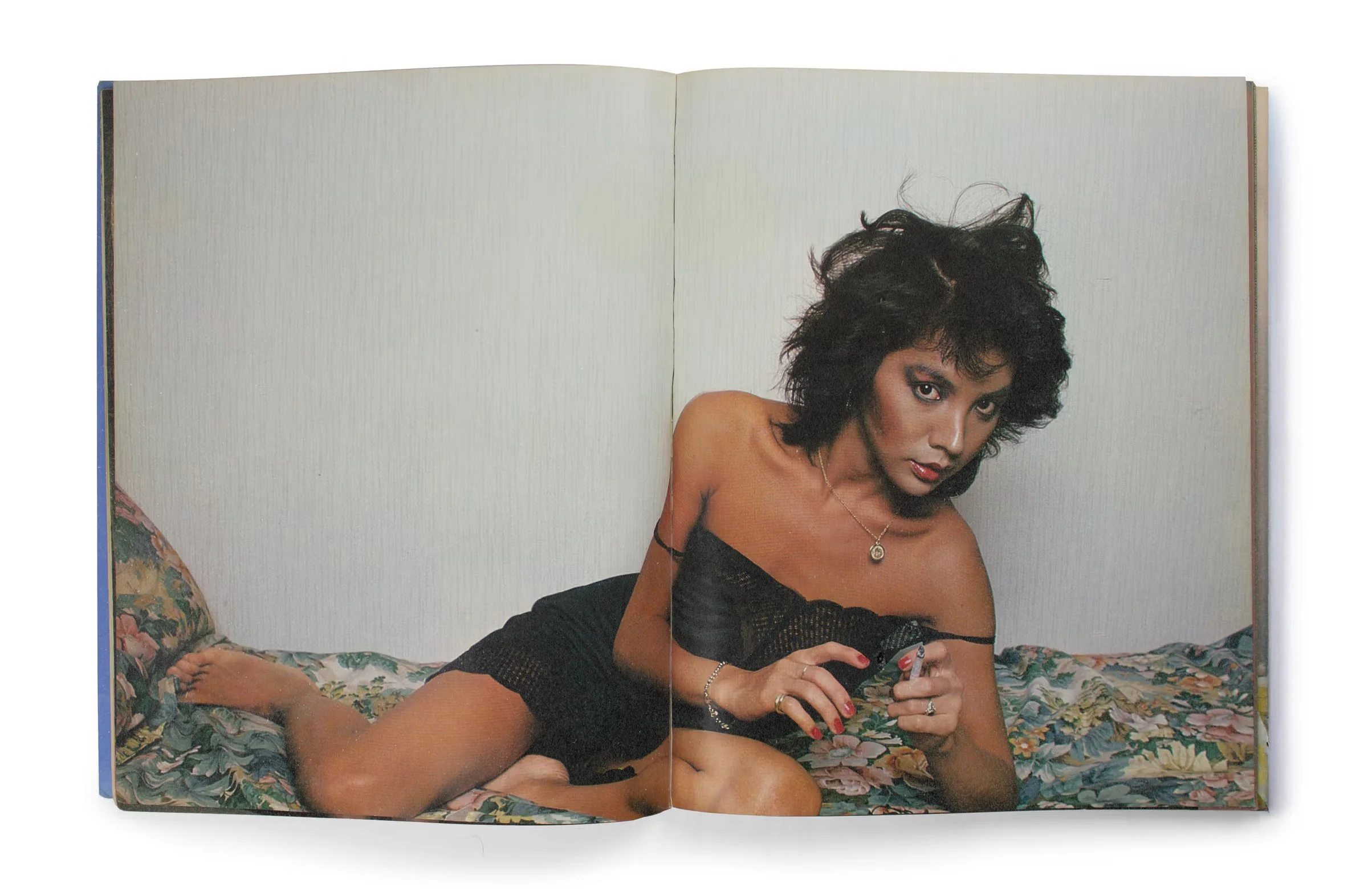

Red Flower, The Women of Okinawa, 2022, ©Mao Ishikawa

Red Flower, The Women of Okinawa by Mao Ishikawa

Named after the native Okinawan hibiscus that Ishikawa loves, the book is a powerful chronicle of the strong and beautiful Okinawan women she met while working at military bars catered to Black American soldiers in Koza city and Kin town. What began as an intention to photograph US soldiers gradually shifted as Ishikawa became drawn to the freedom, intimacy, and vitality of her fellow bar girls. In the sprawl of narrow, cramped Okinawa—marked by the historical wounds of double-colonization—Ishikawa traces the love stories and tender communities that emerged between Black American soldiers and local Okinawan women, two marginalized groups navigating life in 1970s Japan.