Ling Long Magazine: An Escape Route or an Instruction Manual?

Words by Liv Franks

If you were to peek into the handbag of most middle-class women in 1930s Shanghai, you would be presented with a pocketbook-sized magazine. Ling Long (Linloon in English translations) was in print from 1931-37, and widely circulated amongst society women and students alike. Its editorial board was a mix of men and women who covered lifestyle topics. Paradoxically, their perspectives ranged from radical feminism to staunch nationalism.

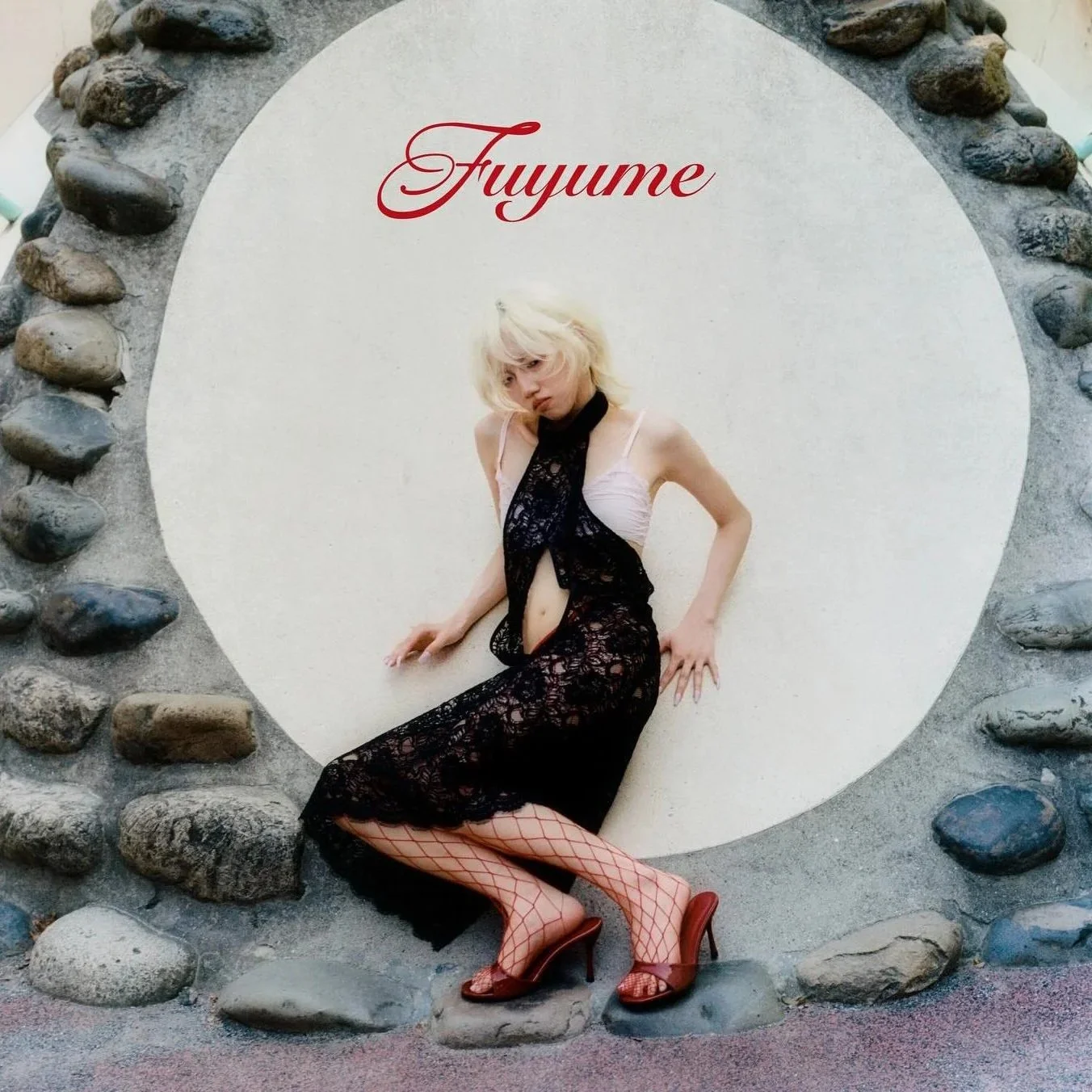

Throughout the 1920s and 30s, the materially driven concept of the New Woman was sweeping across the globe. Despite the history of restrictive roles for women in Chinese society, the women of Shanghai were not going to be excluded from this movement. Living in an increasingly metropolitan Republican Era Shanghai, they too bobbed their hair, raised their hemlines, and dreamt of being movie stars. As a result, Ling Long covers showcased cinematographer Miss Zhang Wen, girls competing in the hurdles, and even swimsuit-clad ladies at their local lidos.

The magazine’s circulation in port cities, for the low price of 21 copper coins, meant that Ling Long cultivated a wide readership amongst the middle classes. These readers were exposed to a litany of adverts, celebrating a new leisure culture entering China. Moreover, the adverts originated from Western countries, like the German camera company Agfa. Fashions from Europe and the US also increasingly featured in the magazine, and were modelled by Western and Chinese women. We know this because Columbia University and Heidelberg University have painstakingly digitised much of the collection, and it is available to view online.

Despite a heavy Western presence, Ling Long seemed ultimately ambivalent to the West. At most, some writers would try to distinguish themselves from the typical Western woman. For instance, in the 1933 piece ‘Nationally Produced Female Stars and Foreign Female Stars’: western girls wanting to become film stars ‘must know how to dance, ride a horse, shoot, drive a car, swim, etc’, whereas ‘swimming is not so important [to a Chinese girl] but given the opportunity, she must wear a 1934 swimsuit showing off her curved beauty to arose desire.’ Evidently, not so different after all…

1935, Sanhe Publishing Company, Ling Long, Issue 184, Columbia University

That is to say, Ling Long instructed women to fulfil a prescriptive role in society. Yes, it was undeniably different from what the New Life Movement prophesied, or from the upbringing their mothers and grandmothers would have considered. However, it still emphasised the elegant, delicate nature of women, and the importance of their beauty (just within a more westernised aesthetic). Whilst they wrote about driving cars, and living alone, they had to do so whilst maintaining a perfectly shiny “do”, and avoid any of that car oil getting on your lovely silk gloves, too.

1937, Sanhe Publishing Company, Ling Long, Issue 273, Columbia University

Whilst, from a modern perspective, a magazine platforming feminist theory would be considered politically minded, Ling Long generally steered clear of holding an explicitly political opinion. For instance, printing continued during the aerial bombardment by the Japanese in 1932 without a mention. They received criticism from the New Life Movement that advocated the return of traditional housewives and mothers to the women of China, but yet did not change.

We cannot deny the fact that Ling Long was a magazine at odds with itself. From one moment printing instructive articles on how to prove one’s virginity to a potential suitor, to extolling the empowering possibilities of a life alone. There is not a singularly supported viewpoint across the articles. They celebrate the empowering concept of a life after divorce, but still seem to imply divorcees are tainted women. It was undoubtedly radical to have women writing about sex, and yet this was undermined by the assertion that “getting entangled with men harms their gentleness and coyness”, as if they had lost something tangible through taking autonomy over their sex lives.

1937, Sanhe Publishing Company, Ling Long, Issue 291 Scanned by Columbia University

Ling Long was written by the young women of Shanghai. Women who faced censorship, political turmoil, and increasing access to western material, yet they embraced the cinema, gambled, and cared about what her classmates said about her hairstyle. The very name of the publication speaks to this dissonance. Ling Long has etymological roots in the Ming Dynasty describing the sound of jade clinking against one another. The contradictory articles create a dissonance between themselves, just like the jade jewels bashing into one another, and in doing so, Ling Long claimed it was able to morph into “one and only tongue (and voice) of women” living in Shanghai. Ultimately, what was contradictory about the magazine’s content mirrored the contradictions of the modern woman’s life during the 1930s.